After Noam

A program of reeducation

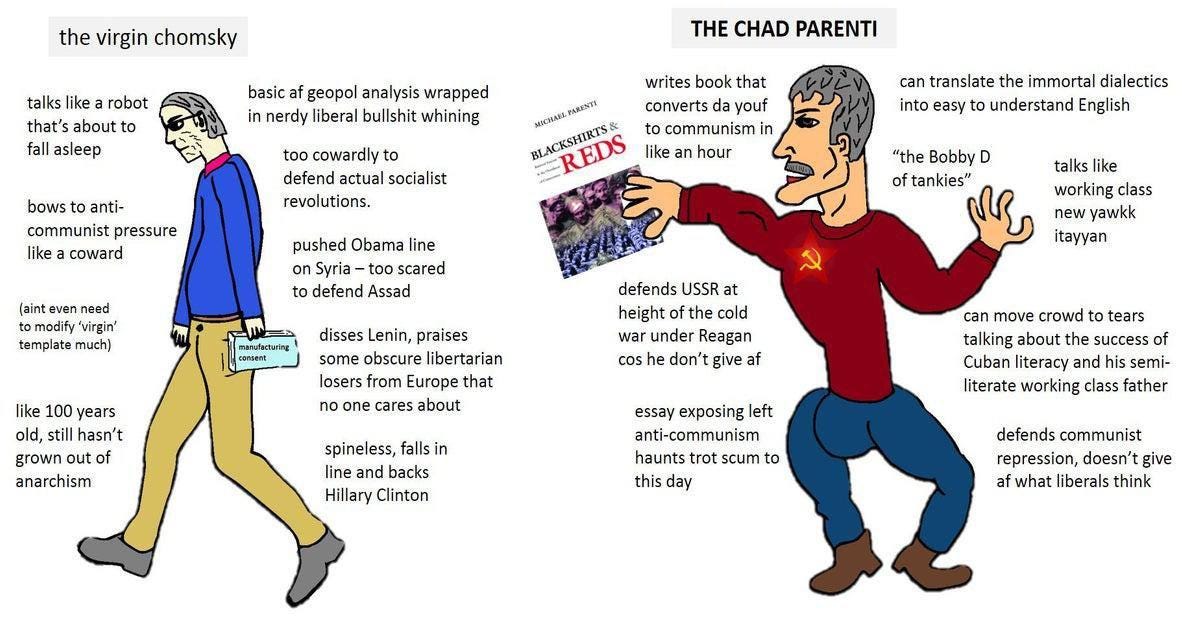

During the first few rounds of Chomsky Epstein revelations - indeed even before - I’d been seeing, from leftists on social media, various versions of the meme that Parenti was the real leftist and Chomsky, mere controlled opposition.

As the revelations rolled out, many said that they knew it all along, that they had long resented Chomsky’s anarchist / libertarian politics, the things that he said against the Bolshevik Revolution and the USSR, against “conspiracy theories”, against BDS and the right of return, in favor of the “two-state” dead end.

But Parenti wasn’t my pathway to activism. Chomsky was. I didn’t know it all along.

Discovering Chomsky

I grew up reading the Canadian daily newspaper my dad subscribed to, The Globe and Mail, every morning, for as long as I can remember, in disgust without knowing why. As a teenager, I stumbled on Eduardo Galeano’s Memory of Fire in my public library; Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj in a shopping mall bookstore. I wrote a high school history essay about Mao Zedong. I read about the life and death struggles of the revolutionaries of the past. But these people were literally leading warriors into battle. I couldn’t see a way to emulate them in my own life. About a year later I found Chomsky’s Deterring Democracy in a university library. Even after reading about revolutionaries, there was something new in that experience. It felt like the mainstream media that had been playing in the background my whole life had encased my mind in glass and Chomsky’s writing shattered the glass. I didn’t know it was possible to write like that, in that style, without the reverence and deference for American power that was an invisible part of every word and image on cable TV and newspapers at the time. I tracked down all the books I could find by Chomsky: Turning the Tide, Year 501, Culture of Terrorism, World Orders, Old and New, Towards a New Cold War, American Power and the New Mandarins. I got into Fateful Triangle and co-authored books like Manufacturing Consent and The Political Economy of Human Rights, later.

It’s only recently that I’ve been hearing people who say that Chomsky never said or did anything special. This is not my experience. To me, there was a lot he did that was special, and I’ll try to get specific about that below. But it wasn’t just what he said and how he went about the writing, but the fact that I could actually imagine trying to do what he did - not leading a guerrilla movement or a satyagraha, but working in science and then trying to make a political contribution through writing. I saw it, and I did it: I’d always liked science and been interested in history and politics and writing, and seeing that Chomsky had done it, I thought I could try to do both.

Searching for Chomsky’s name, I found ZNet on the 1990s internet. I joined their online forum community, volunteered for their website, started my political writing journey there, attended their summer school, taught at their summer school, and became friends with people who were also major political and intellectual influences on me. This became my main political engagement for more than a decade and a half. It’s hard for me to express how proud I was to be associated with Z and with Chomsky specifically. It’s difficult to put into words how much of Noam’s ideas, methods of working, teaching style, and even interpersonal and activist approaches I consciously tried to absorb. If there was such a thing as a “Chomskyite”, I was one. Maybe I still am.

An elite defector

I never had the delusion I would reach either the scientific heights or political influence that Noam did. Everyone’s capacities are different, we were from different eras, and we started in different places. These are realities of class society. In my life I’ve met people who started with fewer privileges than I have had who couldn’t get a break: getting a ride somewhere or transit fare, fixing a broken computer or getting a form printed became huge challenges. I’ve also known people for whom everything works out, who could easily do things that would never occur to me as being possible or feasible.

This is a fundamental thing I don’t think people understand about Chomsky: He’s a member of the elite who became a dissident. He was always going to have a high academic and public profile. He published his writing in elite journals. When he talks about even the most genocidal US policies with total disgust, he uses the first person “we” to describe the US - “we bombed”, “we overthrew”, “we slaughtered”. Back in 1967, when he was a decade younger than I am now, he was on a panel with Hannah Arendt and Susan Sontag - on the stage with the most prominent intellectuals of the time. Coming from where he comes from, there is something of the magician that betrays his illusionist profession to reveal how the tricks work backstage. He focuses his criticism on US imperial intellectuals, because he knows (and hates) how they think. Not, again, something that others who are not of his background could emulate.

Chomsky has argued - I took his word for it then and I disagree with him now - that US elite culture didn’t really support Israel until after the 1967 war. In his words, he was “driven out of the mainstream” over the Palestine Question around 1970, after - according to his analysis - the post-1967 consolidation of Zionism in the US. By then he was already so prominent that his being “driven out of the mainstream” helped to generate an alternative media ecosystem, with Z Magazine’s growth in the 1990s being due in significant part to the fact that they were publishing Chomsky. And not only Z.

Chomsky’s enormous standing in the US intellectual class and in the Jewish community meant that when he took up opposition to Israel, it had the effect of giving the rest of us some kind of permission to do the same. Thanks to decades of struggle by Palestinian activists, the Palestine movement has reached the maturity to follow Palestinian voices. But in the early 2000s, those of us “Palestine people” who were neither Palestinian nor Jewish, found ourselves looking to Jewish voices like Chomsky, the late Tanya Reinhart, and others, to quote [1]. When I went to occupied Palestine in 2002 with the International Solidarity Movement, it was after reading an article by Chomsky’s student Tanya Reinhart called, simply, “Stop Israel!” Thankfully, the movement is finally moving beyond the need for this and recognizing this as an issue for all humanity - for all of us Basel al Araj called “Palestinian in the broad sense” [2]. But in those years, Chomsky had a role in creating that space, at least around here. His punishment for breaking this taboo was being “driven out of the mainstream”.

The US establishment may have regretted driving Noam from the mainstream. Many decades later, they absorbed him back in.

Demystification

No one can decide where they come from nor the talents they’re born with. There’s nothing wrong with being from an elite family, especially if you become a dissident. Or a revolutionary - wasn’t Castro from a big family? Nor is that something that can be learned, or emulated. What then, are the elements of the “Chomskyism” that I am lamenting?

Reading Chomsky’s books, you’ll come across phrases like, “as any six year old would know”, “a three year old could understand”. These kinds of statements are popular in the natural sciences, when trying to distinguish between easier and harder concepts. Chomsky’s agenda was to demystify social and political affairs. He didn’t want ordinary people to be intimidated by academics or elites who claimed to rule because they were so much smarter. No, Chomsky always argued, these were things anybody could learn and do, and you didn’t need complex social theories. His scientific ideas, which I know only a little bit about, were also along these lines - that human capacities like language were the endowment of everyone.

First Principles

Another famous phrase of Chomsky’s is the “elementary moral truism”, which was that “we should judge ourselves” (“we” meaning the US) “by the same standards we judge our official enemies.” Chomsky also repeatedly referred to the “elementary moral principle” that it’s only moral to focus on things one can affect - hence, people of the US ought to focus on US crimes, which they are supposed to have responsibility for, and not the crimes of enemies, which, however awful they may be, are not your responsibility any more than lamenting the crimes of Genghis Khan is your responsibility. In 2026, it is pretty clear that ordinary people in the US have much less ability to affect foreign policy than is implied in this principle and that the crimes committed by the genocidal, pedophilic Epstein class might as well be being committed by foreign occupiers or aliens since ordinary people have zero ability to influence them. Nonetheless, Lenin also held something like this idea [3] in the lead up to WWI, arguing that instead of joining their respective ruling classes in going to war against other workers, socialists ought to take the battle to their own national ruling classes.

Like building a mathematical system, Chomsky wanted to present a small number of “elementary moral truisms” which reveal the injustice and immorality of US foreign policy. Demystifying elites is a good thing to do. Teaching that understanding politics is within the grasp of anyone is also a good thing to do. It’s possible to overdo it – if you tell a student that something they are struggling with is actually simple, it might be empowering, but it might also be disempowering. Chomsky also overreached when he claimed that Marx’s political economy was overcomplicated by a class of Marxist intellectuals. As Chomsky knew, some elements of political economy are complicated and take long and difficult study to understand. It isn’t always mystification.

Using their sources

Another “Chomskyism” is to use establishment sources to refute establishment propaganda. The most devastating critiques are delivered by quoting US and Israeli officials themselves. This was a powerful technique worth using, but it can be overused and devalue local sources and people on the ground.

The Analogical Method

In his tribute to Noam for his 95th birthday, Z Magazine publisher, 1960s antiwar activist, and former MIT student of Noam’s Michael Albert described what he thought admirable and remarkable about Noam. In terms of his work and teaching style, Chomsky was remarkable for giving time to everyone who approached him with a sincere question, answering emails all day, every day. He especially supported activists and activist groups. Michael also talks about how, in addition to reading fast and a lot and remembering a large amount of what he reads (qualities that others have, if perhaps to a lesser extent), Chomsky has a skill with employing analogies:

“He would switch from talking about the U.S. in Vietnam (then obscured by emotional preconceptions and prejudices that the U.S. could do no wrong) to the role of Russia in Eastern Europe (where an American could see invasion and imperialism more clearly). He would switch from discussing the possibility of a U.S. invasion of Afghanistan (which deeply-held axiomatic U.S. beliefs biased against recognizing since the U.S.was never the bad invader) to the possibility of Iran invading Afghanistan (easier to conceive for someone from the U.S.). He would switch from assessing the criminality of the U.S. punishing Afghanistan’s whole population for their country housing terrorists who attacked the U.S. (confused, after all, how could we be criminal) to Britain (if it had done so) punishing the U.S. for housing and financing IRA acts in Britain (easy to analyze since of course anyone else can be criminal). Or he would compare the media emphasizing 9/11 as terrorism but not seeing the U.S. embargo of Iraq as chemical and biological warfare waged on civilians. He would move from discussing U.S. media dynamics to discussing old Soviet media dynamics, or from discussing U.S. foreign policy to discussing the behavior of Mafia dons, and so on. The analogies would bypass confounding biases to reveal core features and then he would switch back to see them in more difficult to accept circumstances like scientists with thought experiments more generally.”

This, one of the trademark “Chomskyisms”, was certainly useful for breaking through propagandized thinking. Chomsky would use American hatred for Russia or Iran to stump audiences as to why they don’t have that same energy when the US is committing crimes. He compared the silence on the US-sponsored Indonesian massacres in East Timor with the wall-to-wall coverage of Khmer Rouge massacres in Cambodia. For people who didn’t like him, these analogies were the ammunition to insinuate he was an apologist for the Khmer Rouge, or for tankies, to say he hated the USSR. I believe he did sincerely oppose the USSR and in his reading of history, the Bolsheviks prevented a libertarian socialist or anarchist revolution from happening (a reading of history I don’t share, and for which Parenti’s reading in Blackshirts and Reds etc. is much better) but the point of these analogies was much more tactical and pedagogical: it was always to show that if, as you’ve been taught, you hate these actions by official enemies, you should hate these actions by the US (which he would say, “crimes that we are committing”) that much more.

Even though my first exposure to this analogical method was Chomsky, I learned later that Marx used it a century before when critiquing the British Empire’s second opium war. The British used as a pretext that the Chinese attacked their fleet as it headed to the capital where the British Ambassador wished to set up. In an 1857 article in the New York Daily, Marx asked: “Does the right of the French Embassador to reside at London, involve the right of forcing the river Thames at the head of an armed French expedition?”

The Chronological Method

Another key element of Chomsky’s method was the fact that he read the New York Times every day for many decades and was able to hold details, quotes, and historical events. He also freely read primary sources, classic texts, and archives, without any intermediation. Simply by holding on to the chronology, Chomsky was able to debate propagandized people even when they claimed to have life experience. The link is dead now, but one of the most memorable moments for me was a lecture he gave at MIT that I watched on video in 2000 (“The Current Crises in the Middle East: What Can We Do?” MIT. December 14, 2000). An angry Israeli settler in the audience told him she’d suffered under shelling from Lebanon during certain years in the 1970s. Chomsky told her there was no shelling in the relevant years and she’d been raised to believe something that wasn’t true - directly refuting someone’s claimed “lived experience”. When some new round of Israeli atrocities would happen in Palestine and Israel would claim they were retaliating, Chomsky would always show up with a chronology of the many Israeli atrocities that had preceded the current one. The lesson for me was that there is tremendous value in simply knowing what happened when.

It turns out, again, that this power was also exercised a hundred years before by Marx. During the so-called “Indian Mutiny”, Marx wrote extremely detailed military reports for newspapers and refuted British propagandists by showing they were nowhere near the atrocities they claimed to have witnessed.

Limitations

Because Chomsky did indeed read a great deal and write at least a bit about every place where the US committed crimes (which means everywhere in the world), it’s easy to miss the fact that he did, actually, specialize in a few places and times: The later stages of the Vietnam war. The Central American wars of the 1970s-1980s. Iraq from the first Gulf War onward. Israel/Palestine especially from the 1970s to the late 2000s. Even when talking about other situations, these would be the main examples he would reach for. His book Year 501, published in 1993, spends most pages on the second half of the 20th century. For the most part, when Chomsky uses history, it starts in WW2. People who liked Chomsky or disliked him may not have realized these limitations.

With Israel/Palestine in particular, not really looking at the early Zionist movement, the Balfour Declaration, the so-called Arab Revolt, and the Nakba, but starting history in 1967, leads to massive distortions. The limited window misses how the Zionists, mostly from Germany and Russia, worked with the British Empire before they went over to the US. Chomsky argued firmly that the US was in charge and Israel subordinate, and the Israel Lobby irrelevant. It’s probably time to revisit all of these views.

Too many interviews

Another limitation: Famous for answering every email, accepting every invitation, and taking every interview, Chomsky probably took too many interviews (we could call Chomsky of the interviews, Chomsky-I). Most of the “gotchas” people have about Chomsky, most of the “I knew it all alongs”, are things Chomsky said in interviews. No matter how good you are in interviews, a claim in a piece of writing that you sat and composed and edited will be of a higher standard (this includes lectures you wrote up beforehand). One writer I met because of Chomsky and Z once said something like “we’re never any better than what we write”.

Chomsky did start slowing down in the late 2000s. I think the last single-authored book that Chomsky wrote - as opposed to collections of articles or interviews - was Failed States, in 2006. I had often written to him - mostly through the Z boards but sometimes through email. I mostly stopped writing to ask him questions, not wanting to add to the burdens of someone in their 80s, whose wife had died in 2008. I can’t understand or relate to people who tried to co-author books with him when he was in his 80s and 90s.

After all, I’d read his books. I should be able to figure out what he would think of a new situation without asking - and I should definitely be able to figure out what I think.

As I became more of a “tankie”, I thought, if Noam were younger, and in these times, he’d probably be one too.

The Consent of the Governed

Chomsky’s theory of politics, explicitly stated throughout his writing, is that all elites, even the most violent, must depend to some extent on the consent of the governed. This theory is why Chomsky’s political work was so focused on attacking propaganda - for it is through propaganda, not solely force, that consent is won.

Gandhi said something similar in his time. How could hundreds of thousands of British rule hundreds of millions of Indians, he asked? Only with the cooperation of Indians themselves. Hence, for Gandhi, and for Chomsky, social struggle was about organizing the withdrawal of consent. When Chomsky himself participated in militancy, it fit this theory - organizing tax resistance against the Vietnam War. Whether seeking reform or revolution, the role of the activist was to threaten or actualize the withdrawal of consent until elites gave up what the people wanted.

It’s a compelling theory and I truly thought it was how the world worked. Chomsky counterposed (again more or less explicitly) the theory of withdrawal of the consent of the governed against what he called “Leninism”, the organization of the working class to overthrow the capitalist (bourgeoisie) through unions, the Party, and ultimately armed struggle. The theory of withdrawal of consent was also counterposed against the idea of national states using armed force to defend their sovereignty (which I think Chomsky understood to be a necessary evil).

In this sense, even if he is on record saying he was not a strict pacifist, the author of an essay praising “The Revolutionary Pacifism of AJ Muste” could be understood to be a proponent of nonviolence theory.

For my part, I have come to the conclusion that most nonviolence theory and ideology is ultimately aimed at the Palestine question and specifically at the delegitimation of Palestinian armed resistance to genocide. I have also come to the conclusion that the Palestinian experience, and specifically the 2018 Great March of Return, are as close to a controlled experiment as exists in human affairs, proving scientifically that nonviolence theory is false.

Through the genocide, the response to the encampments, and the Epstein revelations, Western elites have been open that they don’t give a shit about the consent of the governed. We are cattle to them.

I don’t want to convince or wring reforms from these genocidal pedophiles through the threat of non cooperation. I want them gone. I will be discarding this tenet of “Chomskyism”.

Chomsky-B and Chomsky-E

The Chomsky of the books (let’s call him Chomsky-B) was gone before Chomsky befriended Epstein (let’s call the post-Epstein version Chomsky-E).

From Chomsky-B, I will keep the first principles, demystification of intellectuals, the use of establishment sources for critique, the scientific outlook, the analogical method, and the chronological method. I will discard the theory of the consent of the governed and the nonviolence theory.

Chomsky-E is someone I don’t recognize, someone I never knew.

At the end of Robert Barsky’s 1997 biography, Noam Chomsky: A life of dissent, the biographer describes Chomsky in 1990 at a bar in Scotland after giving a talk to activists and unionists. There were 330 who attended the talk, and Chomsky wrote about them that many were “unemployed working class, activists of one or another sort, those considered to be ‘riff raff’, the kind of people that I like and take seriously.”

What a contrast to flying the private jet with Epstein, the photo with Epstein’s butler in Paris, the Manhattan hotel, the “lovely apartment” in New York, “fantasizing” about the Caribbean island, chatting with Ehud Barak, dinner with Woody Allen, “a great artist”. Michael Albert described Chomsky as honest to a fault, which was also my sense of Chomsky-B. What a contrast with telling journalists that his association with Epstein was “None of your business. Or anyone’s.”

Even with a sharp mind, Chomsky needed to retire, and he did. He should have retired sooner. He retired back into the elite from which he emerged, and that elite turned out to be even more vile than any of us believed.

Notes

1- One evening around 2006 or 2007 a Palestinian academic and I were giving a talk in a small room at an Ontario university. During Q/A, a member of the mostly Arab audience asked us why we hadn’t also included a Jewish speaker on our panel. This wasn’t unusual.

2- Even though the Palestine movement has plenty of quarrels with Chomsky, over BDS, the one-state solution, and the right of return, the fact that Israel/Palestine was a central focus of Chomsky’s meant that most of us found ourselves relating to and reacting to Noam more than Parenti - whose politics on the issue were good, as far as I know, but for whom it was simply not as much of a focus.

3 - With important differences since for Lenin, “we” was always socialists, whereas for Chomsky “we” was the US itself.

I, personally, think it's ridiculous for us to be expected to believe that Noam Chomsky was just a naive and trusting old man who didn't do his due diligence in looking into Epstein's background, and believed him when he said his teenaged "girlfriend" was of legal age. Nothing about Chomsky, his intellectual curiosity, or his prolific output of work, would ever lead me to think of him as gullible. I just think that stupid letter was an obvious whitewashing attempt, and the main reason I think that is BECAUSE I read so much Chomsky.

I got a notification around 11:45 p.m. on Saturday February 7 that Valéria's letter had just been published to Aaron Maté's Substack. I commented by 11:56, furious at the way I felt this was an attempt to manipulate the public and downplay the relationship Noam had with an already convicted sexual predator of children. A few people commented, agreeing with me, and by 12:30 a.m., Aaron Maté disabled comments on the piece. But I learned, from Noam Chomsky, that the best way to bury an important piece of information that has to be released to the public is to put it out at a time when people are busy, like White House press releases at 5 p.m. on a Friday. This letter was released close to midnight on a Saturday, knowing that on Monday morning Oversight would be viewing the unredacted files, and the Chomsky letter would be mostly lost in the sauce.

I don't care for Chris Hedges, he seems insufferable and smug, but by Monday he was saying the same thing I was, that Chomsky had to have known. And I believe the victims, who said that Jeffrey Epstein never went anywhere without at least one of the girls, that he never lied about it or tried to hide what he was doing, that he made everyone sign NDA's, and that everyone who knew Jeffrey Epstein knew he was a pedophile. I do not believe that a brilliant man who understood power dynamics so thoroughly he debated Michel Foucault on that topic more than fifty years ago was somehow fleeced by a sneaky pedo.

It all feels like a, frankly, pedestrian attempt to manufacture consent and preserve the reputation of a "Great Man." But history is filled with "Great Men" who were terrible people to women. Through his relationship with Epstein, Chomsky was introduced to Ehud Barak. And Barak is believed to be the unnamed world leader whom Virginia Guiffre said in her memoir raped her so violently, she believed he was killing her. I believe Virginia, and all of the victims, and I have had the unfortunate experience, personally, of being assaulted by a man I knew and trusted and never would have suspected was capable of such a thing. But this is how patriarchy operates. Men will protect other men at any cost. And the prestigious reputation of a man will always come before the actual lives and safety of girls and women in a patriarchal society. And Noam Chomsky, for all of his years of research and study and pontificating on power dynamics, failed to ever really address patriarchy and gender as the most widespread form of oppression ever. So, while it is disappointing, I find the whole thing very icky, and it absolutely does taint my esteem of not only Noam as a person, but his work. I refuse to separate the work from the person, I'm not fucking doing that. Patriarchy says that a man's contribution to culture and academia is so invaluable, we should overlook their extreme moral shortcomings. Patriarchy is why the world is falling apart at the seams. And I, for one, have been disillusioned of the belief that patriarchal men have any clue how to fix and reform a system that they uphold, were molded by, and benefit from. Kill your idols. Burn it all fucking down.

After Chris Hedges wrote that Noam knew about Epstein's crimes and didn't care, it was very difficult to understand my personal hero (Noam). But, as I reread "Deterring Democracy," I was reminded (just like you Justin) why Noam was so important to me. He took a principled stand against a mass media that once again serves the interests of power from Gaza, to Venezuela, to Haiti, to Iran, to Somalia, et al. I'm glad you placed it in the perspective of Chomsky-B and Chomsky-E. I will continue to learn from Chomsky-B, and refer back to him. While I turn my back on Chomsky-E that got on the Lolita Express.