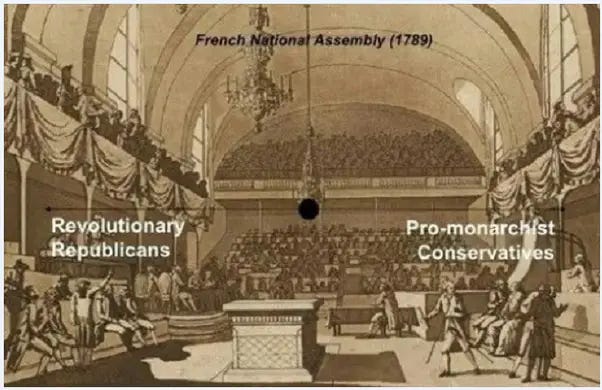

As long as the French and Haitian Revolutions have any bearing on our world, the categories of “left” and “right” will continue to be relevant. In other words, the “political spectrum” established by the seating arrangements at the French National Assembly of 1789.

Unfortunately (as I will argue), the concreteness of seating arrangements has given way to some unhelpful abstractions and analogies.

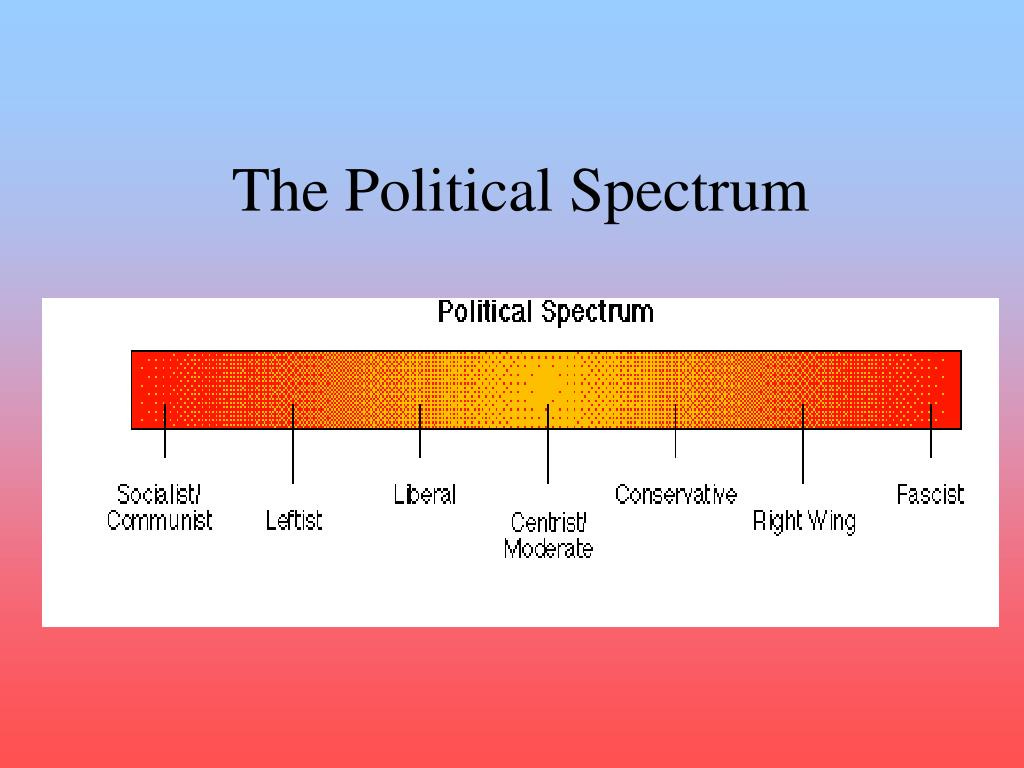

Until recently, my own idea of the political spectrum was pretty basic, something like this.

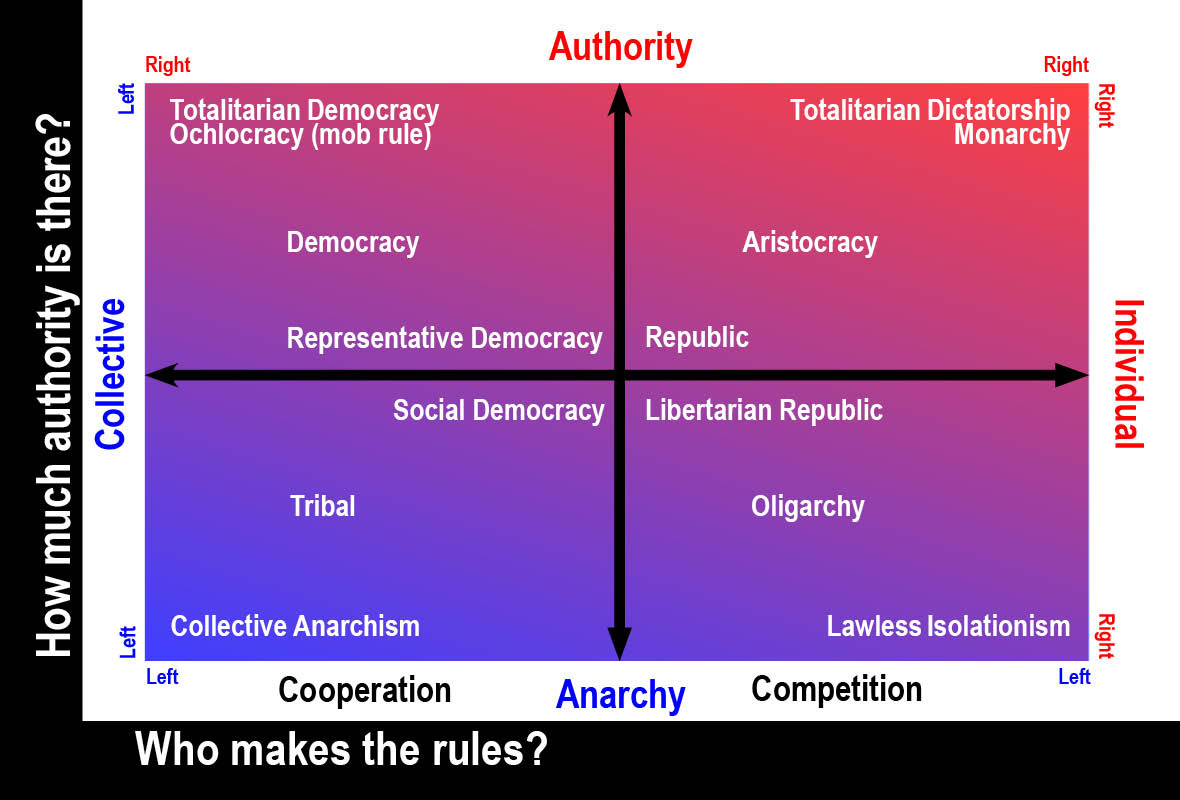

You’ve probably been seeing the ones with the quadrants on the web recently:

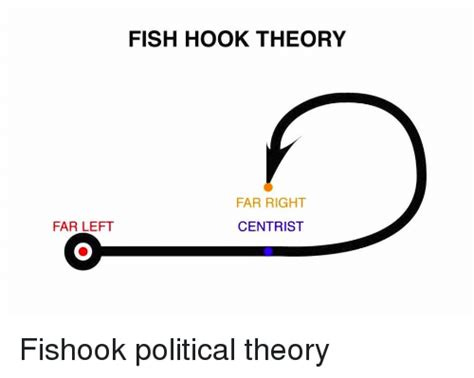

Or the horseshoe.

It may be better than the horseshoe, but I don’t even believe in the fish hook.

As with most attempts to graph political phenomena, I find these conceptual graphs to be much less helpful than writing out the concepts in full words and sentences. This is not a case of a picture being worth a thousand words. More like a picture needing a thousand words to undo the confusion it causes. Political relations - of commonality, difference, or opposition - cannot be mapped on a one-dimensional or two-dimensional spatial grid without missing most of the point, or worse. The adjacency relations don’t hold. The topology doesn’t make sense.

Even if I find the spectrum diagrams dubious, though, I find value in both the history and the labels. For most of my life, as I said above, I understood politics in terms of three:

Leftist - Liberal - Conservative

In Chomsky’s 1970 lecture, Government in the Future, he argues that leftism (he calls it socialism) is the logical conclusion of classical liberalism. Norman Finkelstein has a lecture on JS Mill arguing that the left needs to learn more from these classical liberals. On that basis, I did get the idea that leftist and liberal were topologically adjacent. For similar reasons I had an idea that, e.g., proportional representation in Canadian elections would lead to a stable left-liberal majority consisting of Liberal + NDP voters. On my own, especially after the last election in Ontario, I came to think it just as likely that proportional representation would lead to a stable liberal-conservative majority consisting of Liberal + Conservative voters (but I’ll leave that for another time, maybe).

Reading works like Chris Hedges’s Death of the Liberal Class, or Thomas Frank’s Listen, Liberal! I got the idea that liberals were some sort of lazy leftist, and as they abdicated their historic mission, Western leftists ended up with a task that was beyond our numbers and our resources to fulfill, having to take up the kinds of things liberals fight for as well as occupy the expected leftist space.

It was works like Domenico Losurdo’s Liberalism: A Counter-History and Gerald Horne’s The Dawning of the Apocalypse that made me conclude that liberals were part of a different tradition altogether from leftism, that historically, liberal politics are imperialist politics. The vitriol of liberals towards anti war politics when it came to Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Libya, Syria, Russia, etc. was also revealing that the (failed) coalition against the war in Iraq was more shallow than my optimistic hopes for it.

This has been on my mind because the Russia-Ukraine war has wreaked havoc on the spatial, “spectrum” diagrams that try to map political positions relative to one another. The “liberal” is “supporting” Ukraine, which seems to practically mean supporting the destruction of a generation of Ukrainians, the creation of millions of Ukrainian refugees, the poisoning of its land by depleted uranium supplied by the West, etc.. The small anti-war left are accused of “supporting Putin” and, searching the web for military analysis, find “pro-Russia” analyses coming from figures with conservative, right-wing views.

The conclusion isn’t horseshoe theory. Liberals and conservatives share more premises than either do with anti-imperialists. Liberals and conservatives alike believe in Western hegemony and Western superiority, they don’t care about sovereignty or development in the rest of the world, they believe in the jungle and the garden. But when liberals suppressed left antiwar voices, as they have for the past several decades, and invested themselves thoroughly in this war, they opened a space that right-wing voices have filled. Some of those right-wing voices are very knowledgeable about military affairs. They also loathe liberals, loathe leftists, and mostly don’t see a distinction between them.

For leftists who believe, as I used to believe, that liberal and leftist were mere variations on a theme, this raises questions about how to use these military analyses, coming as they do from right-wingers.

One way liberals operate politically is through something Matt Taibbi (a journalist who likes to present critiques of “right and left”) called an “ick factor”. Attaching “ick factors” to (in our lifetimes) Gaddafi, Iran, China, Palestinians, Putin — these act as an early filter on anti war efforts. If whole states, nations, populations, or their visible leaders are “ick”, then anyone should avoid them, and avoid talking about peace with them. The problem with following your “ick” is that since bigger media can sling more mud than smaller ones, “ick” will always be easier to attach to official enemies, whether the narratives are true or false. Avoiding “ick” cannot be a path to sound political analysis. Conservatives don’t care about “ick” and liberals cannot follow their own advice: the liberal pantheon of heroes were all genocidal racists. New liberal leaders that come up through non-governmental organizations or social media stardom inevitably fall in scandals or cash out and move on.

Historically, the left often has a lot of catching up to do when it comes to military matters. In the French and Russian revolutions, revolutionary governments attached political commissars to skilled military officers from the pre-revolutionary government, to make sure the military skills the revolutions needed were exercised in alignment with their politics. Chinese and Cuban revolutionaries built their armies in the course of the armed struggle, in special conditions in unique times and at great cost. These revolutionaries left a considerable body of interesting military theory, but also adopted and absorbed lessons from everywhere, including the enemies of their revolutions.

It’s no surprise that a lot of the better military analysis is coming from right-wingers now. If we have to use it, then I suppose we could do worse than follow the quote from Mao Zedong, which comes via Bruce Lee’s notes. Bruce was talking about martial arts, Mao was talking about directing a war, but I suppose it also applies to watching helplessly while preparing for the possibility of participating in an antiwar movement at some point in the future when conditions are better:

All military laws and military theories which are in the nature of principles are the experience of past wars summed up by people in former days or in our own times. We should seriously study these lessons, paid for in blood, which are a heritage of past wars. That is one point. But there is another. We should put these conclusions to the test of our own experience, assimilating what is useful, rejecting what is useless, and adding what is specifically our own. The latter is very important, for otherwise we cannot direct a war.

-end-

Check out: Excluded Headlines provides a weekly news summary of news from the Global South that was overlooked or downplayed by the mainstream media. By journalist and author, Tamara Pearson.

This is very interesting. I often end up listening to people like Alexander Mercouris or Brian Berletic or Scott Ritter on military stuff. None of those people are Left. But they are anti-US imperialism and domination. Their worldview is kind of "anti-globalist" which I find repellent, but I listen to their analysis anyway

I'm not a big one for "plus oneing", but this is excellent.