This post is inspired by The East is a Podcast’s latest episodes on Libya, featuring Matteo Capasso, discussing the rise and fall of Gaddafi’s revolution from 1969-2011. Sina’s episodes coincided with my own research, with my Civilizations co-host Dave Power, into Italy’s initial invasion of Libya in 1911-12. We did our own episode about that invasion, which culminated in Italy committing genocide in Libya after WWI - and we’ll be returning to the long war there and the genocide in our show.

But what I wanted to do in this post is use the occasion of Sina’s episode to talk about a book that profoundly changed the way I viewed Gaddafi and Libya. That book is the 2012 Slouching Towards Sirte: NATO’s War on Libya and Africa, by Maximilien Forte. When there is a US war and propaganda campaign against a targeted country, I instinctively look for books from different perspectives, including if possible the strongest possible case for the other side. I don’t need anti-war books to be fair and balanced: we’re subjected to non-stop pro-war, biased propaganda. I don’t mind reading biased anti-war propaganda. I can do the balancing myself.

I had read a couple of other books about Libya or touching on it. I’d read a bit about the Chadian civil war in pro-US sources like Burr & Collins’s 1999 Africa’s Thirty Years War: Chad-Libya-the Sudan, 1963-1993. I knew about Gaddafi’s Green Book and his Isratine proposal. So, like any consumer of Western media, I got the impression of a snazzy-dressing, mentally unstable, adventurist dictator. Not so different than impressions of Saddam Hussein provided in South Park: The Movie, or of Kim Jong-Un that you would get from Kim Jong-Un’s Little Book of Calm.

Most of the anti-war material I read didn’t really dislodge this view.

But Forte’s book did.

Whenever any US-based regime change is successful, it is cheap and easy to make the argument that the ousted leader was a strategic failure. I have personally heard such arguments about:

the Afghan communists, overthrown in 1992;

Aristide in Haiti, overthrown in 1991 and again in 2004;

Chavez in Venezuela when he was overthrown for a couple of days in 2002;

Saddam Hussein in Iraq in 1990 and 2003;

Assad in Syria from 2011 on;

Hizbullah in Lebanon (for supporting Assad);

Milosevic in Yugoslavia;

Lula and Dilma in Brazil;

Zelaya in Honduras.

These are just the ones I have personally heard in my own life. I know that such arguments have been constructed about every single leader that’s been regime-changed at least since the early phase of the Scramble for Africa in the 1830s when France grabbed Algeria, and probably before.

Now, the fact that they’re formulaic and repeated in every single case doesn’t necessarily make them false. Nor does it make ousted leaders angels or martyrs. It does, however, impose an extremely heavy burden of proof, so much so that it might behoove readers to reverse the default assumption. Maybe if the regime-changers were lying the last 100 times, they’re lying this time.

For Aristide, the argument went that he shouldn’t have accepted the US intervention to put him back into power in 1995; he should have conducted more repression against those who were trying to overthrow him from 2001 on; he should have conducted less repression against same; he should have been more/less conciliatory; he shouldn’t have asked for the indemnity money France stole from Haiti…

And what about Gaddafi? He shouldn’t have antagonized the imperialists with his bombastic style; he shouldn’t have antagonized them by supporting Palestinian armed organizations, the IRA, the ANC; he should have avoided intervening in the Chad war and the fight with that France-backed government; he shouldn’t have made a deal to try to normalize relations with the imperialists, since they overthrew him anyway…

The implication in all these cases is that there was some set of perfect strategic choices that could have kept the nationalist regime in power and kept the revolution moving forward. Maybe there was. But is this a fruitful use of energy, criticizing the failings of third world leaders facing impossible odds? Our efforts might be more profitably deployed in activities other than criticizing the strategic errors of such leaders.

(That’s not to say there aren’t a few good principles that Third World leaders have learned from hard experience. The Patnaiks distilled a few economic ones at the end of their book, Capital and Imperialism: impose capital controls, survive the CIA coup attempt, impose import controls, stimulate the domestic market, raise agircultural productivity, redistribute land, provide rights to employment, food, healthcare, education, pension/disability for 10% of GDP, don’t apologize for economic nationalism. I might eventually do a post just on these points, but not right now).

Anyway, there are several general retorts to the “X was bad and deserved to be overthrown by the imperialists”.

Is the country better of now than it was under X? (Almost always the answer is disastrously no - Libya is an extreme case, though Iraq, Haiti, and Afghanistan are right up there).

If X was so bad, why did the imperialists overthrow him at all?

The answers to #2 can be found in Maximilien Forte’s book. Here are a few:

Under Gaddafi’s regime Libya’s life expectancy grew from 51 years to 74. Literacy grew to 95% for men and 78% for women, and per capita income increased to $16,300. It was the only continental African nation to rank “high” in the Human Development Index.

Gaddafi supported the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. Mandela told Gaddafi: “your readiness to provide us with the facilities of forming an army of liberation indicated your commitment to the fight for peace and human rights in the world.”

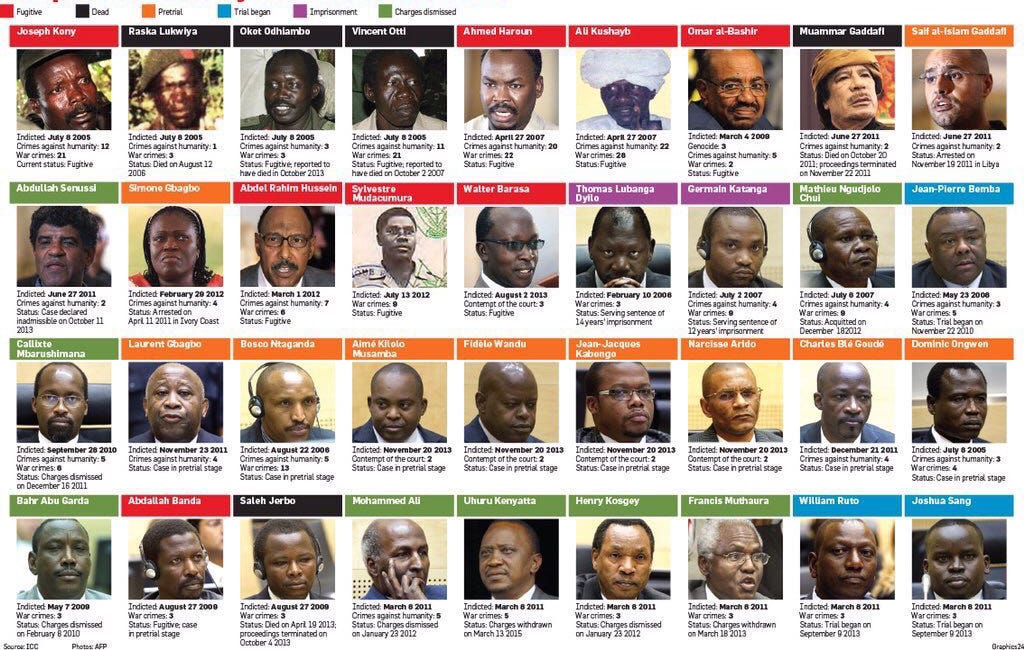

Under Gaddafi, Libya was a major financial backer of the African Union and an advocate for independent, AU institutions including sovereignty over resources, an African Monetary Fund to replace the IMF, and independence from the International Criminal Court which, until it added a couple of Russians to its indictment list, has only ever prosecuted Africans.

Contrast this with the photo of those gathered to overthrow Gaddafi in 2011, above. Notice anything?

Libya under Gaddafi invested around $150 billion in infrastructure and agriculture projects in Africa.

A minor point: Gaddafi treated African leaders and diplomats with dignity (as China does) in contrast with the West which continues to engage in calculated humiliation and indignities of the same leaders.

Gaddafi was a fierce adversary of the US African Command (AFRICOM). After his overthrow in 2011, the US announced deployment to four more African countries: Central African Republic, Uganda, South Sudan, and the DR Congo, and 14 joint military exercises in 2012.

Forte suggests that Gaddafi’s “turn toward Africa” was “arguably a turn away from the Arab world'“. While Gaddafi had worked in many Arab unity initiatives, he gave up around 1999. It was Gaddafi’s Africa policy that got him overthrown.

As always, there’s more. Forte’s book is devastatingly argued, has rich footnotes, and a 30-page reference list. I wasn’t able to emerge from my reading of it with the same stereotyped idea of Gaddafi as an erratic and silly person. Indeed, I don’t even think that the US players that overthrew him saw him that way. That’s a myth for mass consumption, an expression of hatred.

(Another aside, I realized watching pro-war propaganda that while we think of hate speech in terms of screaming, clawing, and gnashing teeth, a lot of hate is expressed through mockery and ridicule. Certainly the caricatures of Gaddafi are hateful.)

When she heard Gaddafi was murdered, Hillary Clinton was being interviewed when the note came in on her phone. Her spontaneous reaction was to say: “We came, we saw, he died.” And to burst into what appears to be a truly satisfied laugh, a rare unscripted moment of celebration for a politician renowned for extraordinary self-control.

There’s nothing to celebrate.