What did Yugoslavia have before it was dismembered?

I know not all of you who read the newsletter listen to the podcast, but we just did a 3-hour epic on the Balkan Wars 1912-1913 that led directly to WWI. Researching it, I came across the dispatches of a war correspondent named Leon Trotsky, who wrote long profiles of all the players, talked to wounded soldiers, traveled all over the region while the wars raged and in their aftermath. Trotsky was no impassive observer, but an advocate for a specific solution to the raging Balkan conflicts of the time: a socialist Balkan Federation dedicated to the economic development of the whole region for the benefit of all its peoples, free from imperial intervention. Trotsky would live to see something like this implemented in the form of Yugoslavia, but Yugoslavia was dismembered decades later by nationalist wars and imperial intervention.

In the podcast I also quoted from Richard C. Hall, an academic who wrote about the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars and came to a similar conclusion as Trotsky:

“The large nationalist state as exemplified by Italy and Germany proved a poor model for the Balkan peoples. No such states were possible, because the nationalist claims of each Balkan state overlapped with those of its neighbors. Every attempt in the twentieth century to realize this goal has led to war and foreign intervention. Only the adoption of a post-nationalist perspective by the Balkan peoples can break the pattern of war and intervention.”

Writing just after the breakup of Yugoslavia, Hall found himself arguing for the necessity of something like it!

I was a teenager during Iraq War 1990/1. I was critical but not in any position to be aware of any anti-war sentiment in my city much less to, e.g., go to an antiwar protest. The first such protests I did attend were during the NATO war for the final dismemberment of Yugoslavia in 1999. A lot of people I knew, including fellow students from the Croatian diaspora in Toronto, actually celebrated when the NATO bombing began. Eastern Europe is not a context where I have a lot of background references in long-term memory and everything I have come to understand about it has been done analytically. Unlike some other parts of the world where I find I have some intuition that I can work from, in this context all I have is reading. As far as my feelings went, I simply felt a lot of horror and tragedy, and could not believe any of the arguments coming from NATO about the necessity of bombing.

I wrote one of my first letters to the editor when a Globe and Mail columnist took the occasion of the NATO bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade to talk about Chinese xenophobia.

I would have written it a bit differently today but you probably recognize the tone.

At the time I thought of the destruction of Yugoslavia as a tragedy of self-destruction. The narrative structure, which I was reading in liberal authors like Michael Ignatieff (who wrote a travelogue of the Balkans as a theory of nationalism in his pre-Empire-Lite and pre-Canadian prime ministerial candidate years), was that these communist states suppressed nationalism which exploded all the worse for having been suppressed, and as the biggest nation in Yugoslavia, Serbia (or, the preferred term, “the Serbs”), had entrapped the others who naturally wanted to break away at the first opportunity. They broke away, “the Serbs” fought back to keep them in, committing so much war and genocide that NATO was forced to bomb them.

It was a compelling enough framework, since it’s impossible to understand any of the belligerents without an analysis of nationalism. What the framework could never explain was what the US was doing in there. The idea that Balkan nationalisms had become so disruptive to the world order that the US was forced to intervene - that was the best available explanation and it was simply preposterous. But it was not until much later that I got a sense of the full role of the US in the breakup of Yugoslavia, and why the US wanted Yugoslavia broken up. To understand all that, I had to go beyond the liberal analysis of rival nationalisms and get into economic analysis.

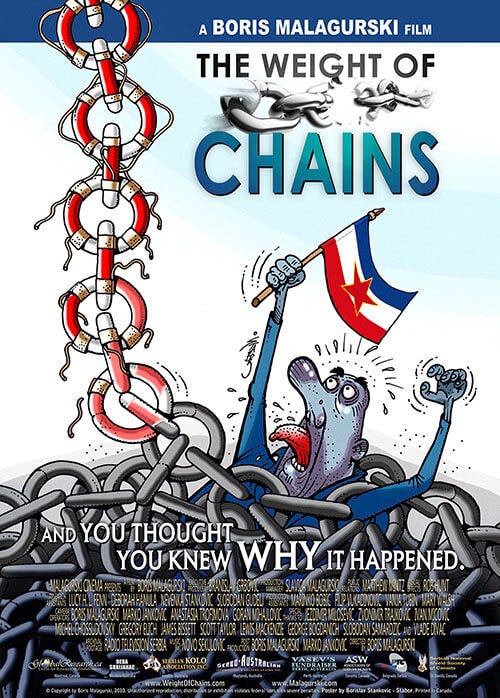

In search of an alternate, anti-war view of the Yugoslavia wars, I read Diana Johnstone’s Fool’s Crusade and Michael Parenti’s To Kill a Nation. But I found the economic arguments put together most effectively (including by these two authors) in a 2010 documentary by Boris Malagurski called The Weight of Chains.

Malagurski grew up in Yugoslavia and links his economic analysis with the experiences his father had working in an industry that was ultimately dismantled along with Yugoslavia - which gives a clue to what was going on.

While it existed, Yugoslavia was a non-aligned country (indeed a founding member of the movement), with an economic model characterized as “market socialist”, trying to combine various elements of economic planning and welfare state protections with market competition. In various ways, it was very successful! Malagurski’s parents, like all Yugoslavs well into the 1980s, had free medical care and education, one month paid vacation, and the country had a 91% literacy rate. With state support and investment, Yugoslavia developed a considerable industrial base, including heavy industries (Malagurski’s film includes considerable detail about a motor plant - which I’ll return to below).

Because Yugoslavia was part of the nonaligned bloc, its leaders sought to maintain good relations with both the Soviet bloc and the West. For the West’s part, the idea of collapsing a socialist state and carving it up never lost its appeal. The collapse of the USSR (which will occupy future newsletters) made it possible. Yugoslavia, like the USSR, tried to reform to taking Western finance. Once indebted to Western banks, Yugoslavia was ready to be carved up.

Malagurski cites a National Security Council memorandum (#133, if you want to look it up), which, under president Reagan, stated a US policy of supporting a “market-oriented” Yugoslavia. In 1988, the National Endowment for Democracy sent advisors to the country, funding another group called the Center for Private Enterprise, which in turn funded the G17 - a group of 17 Yugoslavian free market economists including IMF and World Bank staffers. This Group of 17 ran the government bankruptcy program of 1989-90, forcing cuts to the social sector and forcing public and private enterprises into bankruptcy. About 1,100 enterprises were wiped out between January 1989 and September 1990; the standard of living declined by 18% and unemployment went up to 20% by the end of the decade.

Yugoslavia’s financial crisis was America’s opportunity. When Yugoslavia went to president Bush I in 1989, the US response was to declare that any republic in Yugoslavia could get aid — only if they broke away from the federal republic. Elections would be held only in the constituent republics and aid would only go through them. The US, in other words, used financial aid to begin the breakup of Yugoslavia already in 1990.

The aid worked as intended, and made the financial crisis worse: with inflation at 200%, Yugoslavia couldn’t pay interest on the debt or pay for the raw materials to run its heavy industries. Economic cooperation between republics failed, the communist parties lost elections to the nationalists, and unilateral declarations of independence followed - all of which were quickly recognized by the US. So quickly it was as if the US was waiting for them. The Balkan Wars of the 1990s followed, and the US sanctioned the federal state.

I’ll leave the military questions, which Malagurski covers from his point of view, for another time. Let’s keep following the economic story and US policy.

By 1993, 90% of domestic pharmaceutical production had stopped. Average caloric income was down 28% from 1990 levels, with 1.5 million considered undernourished. Unemployment was up to 60%. Monthly income dropped from $500 to $15. The inflation rate went to its highest in history.

The international financial institutions collected the external debts for each of the constituent republics - they were each saddled with debts, carefully partitioned from the central debt held by the federal republic of Yugoslavia. In 1995, Bosnia unveiled that it would be occupied by NATO and administered directly by the West (which was also Kosovo’s fate). Before the 1999 NATO campaign, the World Bank analyzed the likely effects of a Kosovo war, including plans for occupation.

NATO’s bombing campaign targeted Yugoslavia’s industrial base. A cigarette factory was bombed, later acquired by Philip Morris. The Yugo car factory was bombed, getting rid of competition for Western auto firms. Cement, oil industry, telecom facilities were all bombed.

There is, perhaps, one military note from this period worth making. That is, that while the US successfully bombed various industrial, civilian, and diplomatic targets (including the Chinese Embassy, as mentioned above), militarily the campaign was stalemated in 1999. NATO’s ultimate victory came from the imposition of a diplomatic settlement on Yugoslavia’s president Milosevic, who they later arrested and who conveniently died in in a NATO prison. The settlement was imposed not through victory on the battlefield, but through the threat of a genocidal bombing of civilians. The most detailed account of this is quoted by author Gregory Elich, who cites another source about a meeting between Finnish diplomat and Nobel Prize Winner Martti Ahtisaari and Milosevic:

Milošević took the papers and asked, “What will happen if I do not sign?” In answer, “Ahtisaari made a gesture on the table,” and then moved aside the flower centerpiece. Ahtisaari said, “Belgrade will be like this table. We will immediately begin carpet-bombing Belgrade.” Repeating the gesture of sweeping the table, Ahtisaari threatened, “This is what we will do to Belgrade.” A moment of silence passed, and then he added, “There will be half a million dead within a week.” Chernomyrdin’s silence confirmed that the Russian government would do nothing to discourage carpet-bombing. [6] - June 7, 1999, Il Giornale Milan, Ristic interviewed by Renato Farina.

The meaning was clear. To refuse the ultimatum would lead to the widespread death and destruction. President Milošević summoned the leaders of the parties in the governing coalition and explained the situation to them. “A few things are not logical, but the main thing is, we have no choice. I personally think we should accept… To reject the document means the destruction of our state and nation.” [7]

Once Milosevic signed, Kosovo was put under direct “internationalized” control and the next round of dismemberment of Yugoslavia followed. A German bank took over the banking sector the province. Telecom was sold to German Telecom. A Western consortium took control of the immense Trepca Mining Complex. A local company made butter for 200; Germany subsidized its 300 butter to sell at 150, making Serbia an importer of goods. A steel factory set up with a $600M loan was sold to a US company for $23M. In Croatia, the hotels are owned by German and Austrian companies, the fishing zone was given to the EU/Italy, and the entire island of Brijuni was sold. Bosnia’s new constitution included the Governing Board of the Central Bank being an IMF appointee, and stipulated not to be a citizen of of Bosnia or any neighbouring country. Central Bank independence taken to the extreme: these central banks are so independent that they are totally dependent - on the West.

As for the debt that got Yugoslavia into trouble in the first place: when united Yugoslavia went with its hat in hand to the West in 1988, the country was in serious trouble with $13.5B in debt. By 2010, the West had completely destroyed the country and split it into many republics, whose total debt was… $184B.

Health insurance was privatized, the education system was crashed, health insurance lost, pensions were cut. By the 2010s, close to 40% couldn’t pay their bills and 56% were hungry.

So, returning to the question in the title: before Yugoslavia was dismembered, it had: an industrial base, health care, education (including some of the highest standards in the world), subsidized transportation, and vacations.

I was 14 when NATO attacked Yugoslavia and a German friend of mine had an uncle visit around the same time who was NATO special forces. For a long time, I think because I met this guy and he seemed decent, I was confused about the war (was Milosevic a genocidal maniac or what?). As I got older, I assumed that something nefarious happened to Yugoslavia, but it always took a backseat to other history I felt like I needed to catch up on. This article completely cleared up any lingering confusion I had. Thanks for writing!

Excellent succinct piece!